Coding Our Way to the Moon & Back

Happy Apollo 11 Day!

On July 16, 1969, Apollo 11 launched from Cape Kennedy, propelling Commander Neil Armstrong, Command Module Pilot Michael Collins, and Lunar Module Pilot Edwin "Buzz" Aldrin into space and into history. Much has been said and written about the bold astronauts and rocket scientists who made this momentous mission possible. But we’d also like to take a moment to celebrate — you guessed it — the code of it all.

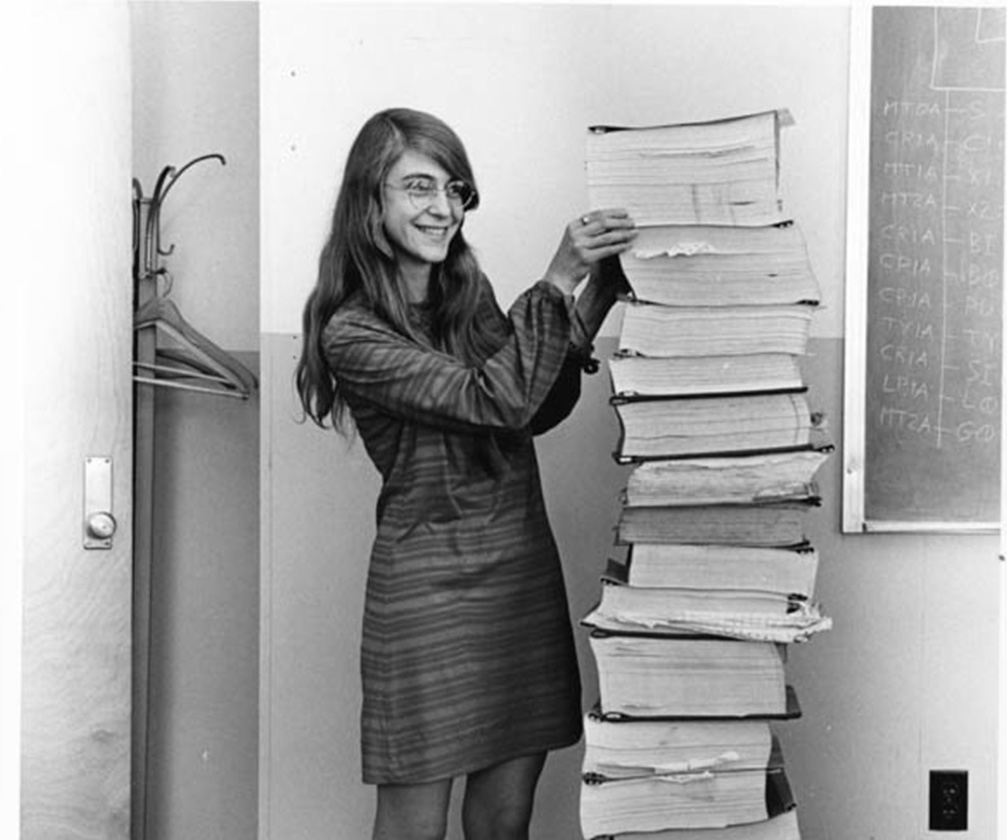

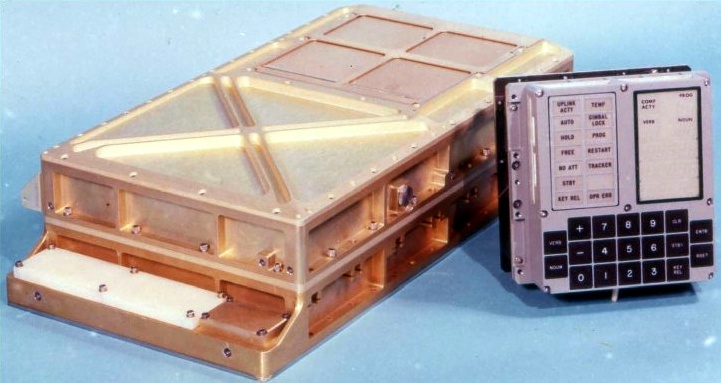

Apollo 11's original source code was developed by computer programmers at MIT in the '60s, led by coding legend Margaret Hamilton. This code was the backbone of the Apollo Guidance Computer (AGC), which astronauts used to navigate and control the spacecraft.

Without the computers on board the Apollo spacecraft, there would have been no moon landing, no triumphant first step, no high-water mark for human space travel. A human pilot could never have manually navigated the way to the moon, as if the spaceship were simply a more powerful airplane. The calculations required to make in-flight adjustments and the complexity of the thrust controls outstripped human computing capacities.

Lucky us: this all-important source code for Apollo 11’s flight computer software was posted in its entirety to Github, a collaborative platform for developers, in 2016. In honor of the anniversary of the Apollo 11 moon landing, we’ve highlighted below some of the most thrilling and surprising aspects of the code that took us to the moon.

No bugs here

Margaret Hamilton, the MIT computer programmer who led the team that created the onboard Apollo software, was an unbelievably capable and precise programmer. As The Guardian noted in an interview with her, “Her rigorous approach was so successful that no software bugs were ever known to have occurred during any crewed Apollo missions.”

No software bugs! It’s incredibly rare for any code — let alone code as complex as the one powering the AGC — to be completely bug-free. Even today, mega-tech companies like Microsoft, Google, and Meta unofficially celebrate “Patch Tuesday” every month, when they release software patches to fix the bugs in their code. Now, we here at The Coding Space aren’t about to judge coding mistakes — we love mistakes for their irreplaceable educational value. That being said, the creation of a bug-less code managed by Hamilton and her team is still a feat worthy of admiration.

Anything but "Sirius"

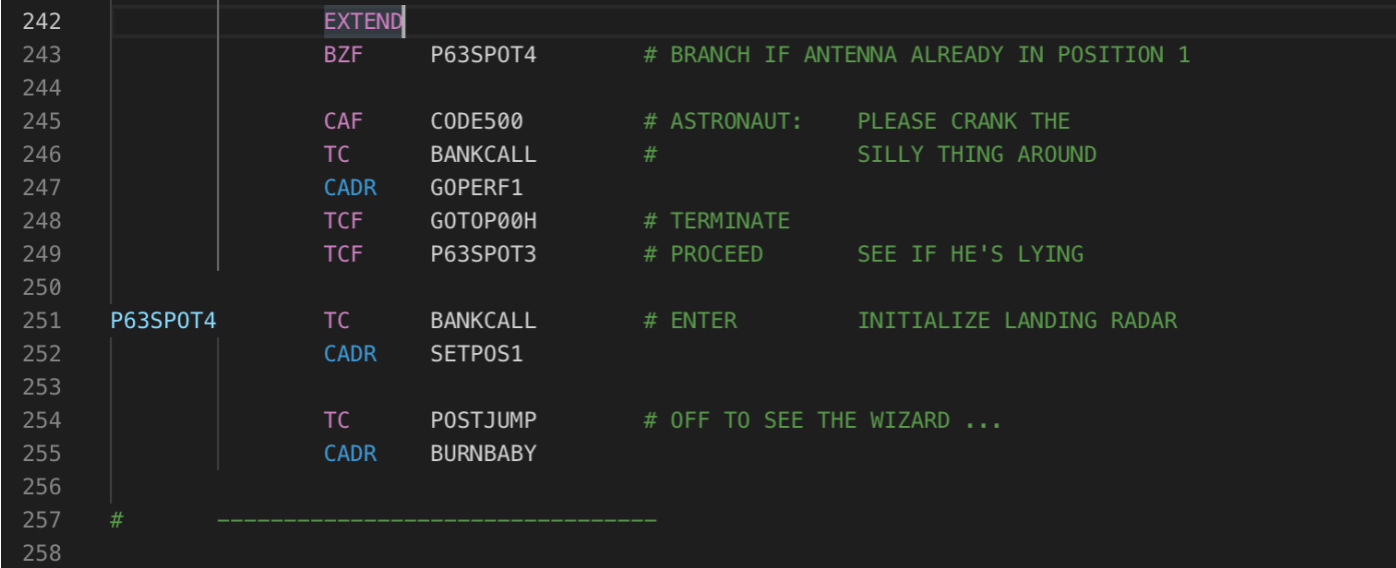

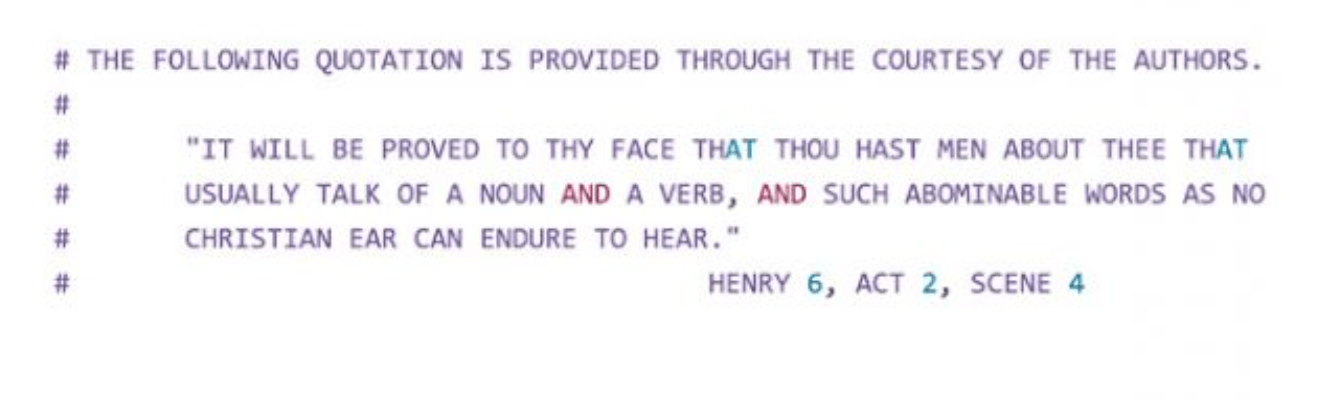

In programming, developers often leave comments throughout their code to describe to readers what the code is supposed to do. However, it’s obvious that the Apollo 11 programmers did more than that. Combing through the AGC source code, coding enthusiasts have found all sorts of easter eggs, consisting of playful messages, puns, and pop culture references. For example, the name for the file responsible for the spacecraft’s main ignition routine is titled "BURN_BABY_BURN," And the file responsible for the spaceship’s keyboard display system is called "PINBALL_GAME_BUTTONS_AND_LIGHTS".

Within the PINBALL folder, there’s an entire quote from Shakespeare’s Henry V. Even cheekier, there’s a comment in the code directing the user to check and make sure the astronauts aren’t lying about following the appropriate commands. There are jokes and secret messages tucked in every corner of the code: it's obvious that the original developers had a lot of fun writing this code, and we have a lot of fun reading it!

Code = Man's best friend

As the spacecraft descended towards the moon’s surface, noise from one of its radars began to feed bad data into the system, directing the spacecraft’s autopilot system towards a dangerous landing spot. The popular narrative of this moment claims that Neil Armstrong, seizing “manual” control away from the glitchy computer, piloted the spacecraft to a safer landing spot on the moon’s surface. Humans did it! Computers are no match for us!

While Armstrong’s instincts as a pilot were undoubtedly spot-on, the true victory of the day belongs to Hamilton and her team’s impeccable code, which was flexible enough to adapt even to unforeseen circumstances. The guidance computer understood it had a problem, but was able to stay functional throughout the descent, dumping the bad information and continuing its more important operations, saving the mission. More importantly, the spacecraft was a fully computerized system — any command that Armstrong gave had to route through the computer. There was no usable manual control! When Armstrong landed on the moon, he worked with and through the AGC, communicating with the computer and directing it towards a safer spot. The moon landing represented a thrilling triumph of human-computer interaction.

The processing power of the AGC is now far outstripped by our smartphones, our calculators — even our microwaves. But what the AGC lacked in sheer power and speed, it made up for in elegance and innovation. The code’s success in guiding the first manned mission to the moon is a testament to the programming team’s ingenuity and meticulousness. We at TCS are inspired not just by these visionary coders, but also the bright young coders we see every day in our classes. We can’t wait to see what amazing programming feats the next generation of coders manages to pull off!